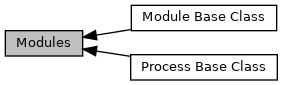

Modules are the programs that users will ultimately use. Modules will do things like pick waveforms and associate events. For this reason, a module can be thought of as a standalone program. Modules typically must do multiple things like send status messages and handle commands. A

process is the basic building block of a module that actually performs the disparate tasks that constitute a module.

Let's explore in greater detail what a process is and must do

#ifndef UMPS_MODULES_PROCESS_HPP

#define UMPS_MODULES_PROCESS_HPP

#include <functional>

#include <memory>

namespace UMPS::Modules

{

class IProcess

{

public:

[[nodiscard]]

virtual std::string

getName() const noexcept;

virtual void operator()();

virtual

void start() = 0;

[[nodiscard]] virtual

bool isRunning() const noexcept = 0;

private:

class IProcessImpl;

std::unique_ptr<IProcessImpl> pImpl;

};

}

#endif

virtual bool isRunning() const noexcept=0

virtual std::string getName() const noexcept

virtual void start()=0

Starts the process.

void issueStopCommand()

Issues the stop command by calling the callback.

virtual void stop()=0

Stops the process.

void setStopCallback(const std::function< void()> &callback)

Sets the stop callback if this process needs to stop the program.

A process consists of a few very simple items

- A process can be started by either explictly calling start or by using the () operator. In this abstract base class, the default implementation of the operator is to simply call start.

- A process can be stopped with stop.

- A process must be able to report whether or not it is currently running with isRunning.

- A process may be provided a callback so that it can signal the uCommand is requesting a program termination. This is typically leveraged by the process that handles local interaction from uCommand.

A potential point of confusion is that a process

can be multi-threaded. What this means is that even though a process will likely be started using something of the form std::thread(process), there still may exist a thread-pool within the process's implementation that enables it to achieve its requisite functionality.

Naturally, it would be convenient to collect all of our processes in one container. This the job of the ProcessManager. Specifically, the process manager is a collection of unique processes. At the time of writing, the process manager is very simple. It basically can hold, run, and stop all processes. In time however, we hope it will do really cool things like detect and restart dead processes.

An important process that you should implement is the command process. One extraordinary benefit of embracing messaging is that you can actually run a module in the background with, say, nohup, and then login to that server at a later time and still interact with that module using uCommand. Note, uCommand uses IPC communication and is only usable by the same user on the same machine that is running the program; this is not a limitation of ZeroMQ IPC's implementation but a security consideration. But why stop there? Since the module can interact locally it can also easily be extended to interact with a privileged user on the network. Again, the module could interact with anyone on the network but again, for security reasons and not limitations of ZeroMQ, we require the user issuing commands to remote modules be privileged.

In parting, note that you do not

need to write your programs using the Process/ProcessManager paradigm. It exists because I find it convenient and dislike rewriting the same boiler-plate code for common tasks like connecting/querying the uOperator or sending a heartbeat. Indeed, none of the code to implement these tasks is particularly difficult to write. What you may, however, find slightly challenging is organizing your code that you can catch exceptions.